When most of us think about “living longer,” our minds don’t immediately jump to calf stretches, single-leg stands, or spinal mobility. We might think about diet, cardio, maybe even a multivitamin or supplement. But longevity isn’t just about what keeps your heart ticking and your brain firing on all cylinders – it’s also about what keeps you upright, moving, and independent as the years roll on.

Mobility, flexibility, and balance are often relegated to the fringes of fitness routines – sometimes as an afterthought, sometimes left out entirely. However, the science is getting increasingly clear – these so-called “soft skills” of movement may be just as critical for long-term health as how much you can lift or how far you can run.

In this blog, we’ll unpack why these factors matter, what’s really going on in the body, and how to preserve (or rebuild) mobility, flexibility, and balance over time.

Why Movement Quality Beats Muscle Size in the Long Game

There’s a simple truth that doesn’t get talked about enough: how you move matters. Not just for today’s workout, walk, or day in the office – but for the rest of your life.

We often think of strength and cardiovascular fitness as the pillars of longevity. And they are – but your ability to squat down to tie your shoe without groaning, to reach into the cupboard without pulling your shoulder, or to step over an uneven kerb without stumbling – these are the important (but very commonly overlooked) parts of good mobility and balance. They’re also the first things to quietly slip away if we’re not paying attention.

What makes this especially sobering is how strongly these qualities are tied to long-term survival.

Balance: More Than Just a Party Trick

A 10-second balance test might not sound like the stuff of scientific revelations, but one study published in the British Journal of Sports Medicine found something staggering: people in their 50s, 60s and 70s who couldn’t balance on one leg for ten seconds were 84% more likely to die from all causes in the following seven years.

Even after adjusting for weight, age, sex, and health conditions, poor balance stood out as a key predictor of mortality. 84% is a huge figure, so it bears repeating.

This doesn’t mean that balance itself is magic – it’s what it represents. Good balance requires muscular coordination, neuromuscular control, proprioception (your body’s awareness of itself in space), and strength. If those systems are faltering, it could be an indication that there’s an underlying health issue to consider.

Flexibility: The Undercover Hero of Healthy Ageing

Often, when thinking about flexibility, people think about the incredible feats performed by professional gymnasts – but this is like thinking everyone who lifts weights should be aspiring to look like Mr or Ms Universe.

In reality, a good working level of flexibility is what to aim for.

New research has found a clear link between flexibility and lower mortality risk. In a long-term study involving over 3,000 adults, those with the greatest range of motion across key joints – hips, shoulders, knees, ankles and spine – lived significantly longer than their stiffer counterparts. Among men, those with poor flexibility were almost twice as likely to die during the study period.

Why? Well, flexibility underpins mobility – your ability to move easily and pain-free. When your muscles and connective tissue are too tight to allow full joint range, it forces other parts of your body to overcompensate. Cue poor posture, aches and pains, inefficient movement, and a higher risk of injury.

And let’s not forget the domino effect. Stiff hips can lead to lower back pain. Tight calves can compromise your gait. Reduced shoulder mobility might stop you from reaching overhead, which – believe it or not – can lead to a less active life. And less activity as you age? This is exactly where health spirals often begin.

Mobility vs. Flexibility: What’s the Difference?

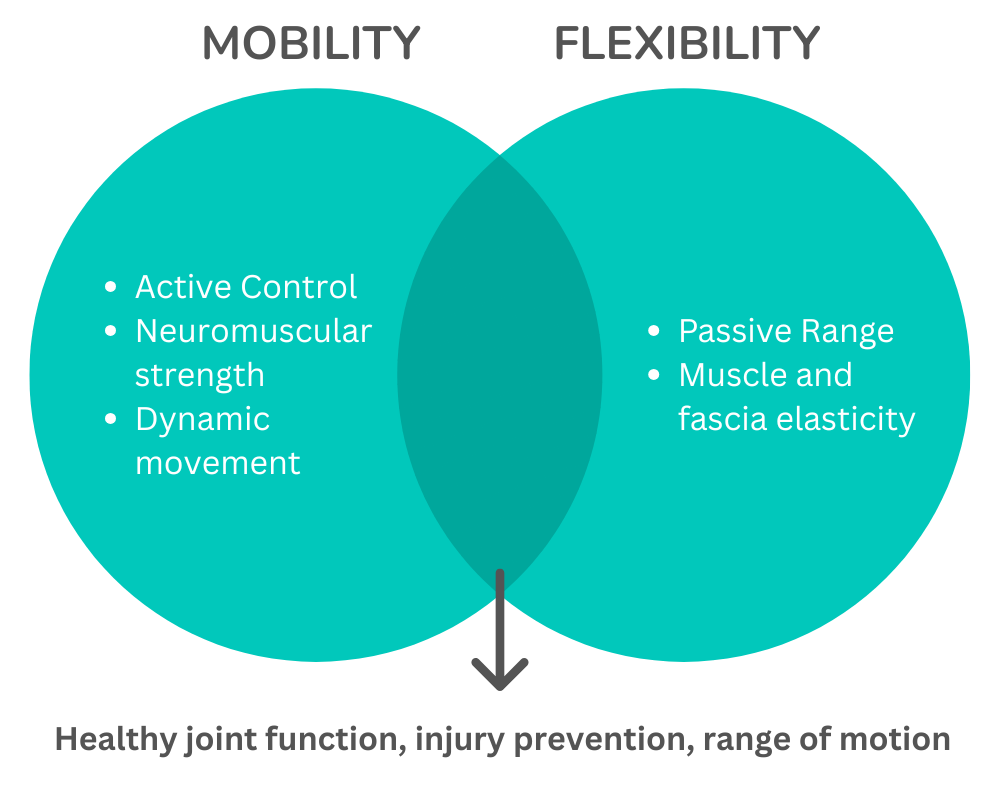

People often use the terms mobility and flexibility interchangeably, but they’re not quite the same.

Flexibility is your passive range of motion – what your joints and muscles can do when gently pulled or stretched.

Mobility, on the other hand, is your active control of that range – how well you can move yourself through it.

Think of it this way: flexibility is lying on your back and pulling your leg towards your chest. Mobility is squatting down and standing up without assistance. You can be flexible but immobile, or mobile but tight – but the ideal scenario is having both.

If you want to age well, you’ll need mobility more than flexibility. But to move freely, you can’t be stiff as a board either. One supports the other.

Recovery, Resilience, and Reduced Risk

Another thing that doesn’t get discussed enough is how your body’s ability to recover from injury or illness is directly affected by how well you move before the incident occurs.

Let’s say you’re in your 70s (when most people’s muscle and bone density is low) and you stumble. If your balance is sharp, you might not fall. If your flexibility is good, even if you do fall, you might land in a way that doesn’t strain or tear anything. If your mobility is intact, you’ll be better able to get up – or respond quickly. And if you’re already active, recovery from any injury will be faster.

In other words, mobility, flexibility, and balance don’t just reduce the risk of accidents. They also soften the blow if something does go wrong – and that’s crucial for staying independent.

Independence and the Ageing Body

It’s a simple equation: the more confidently and comfortably you can move, the longer you can live on your own terms.

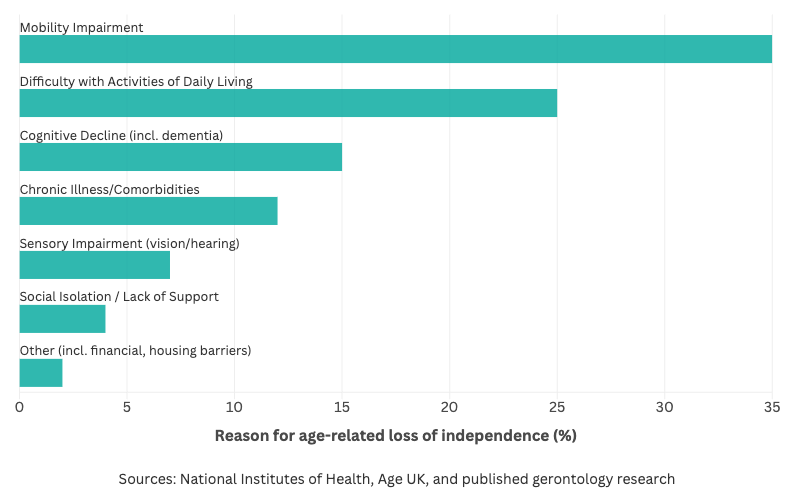

People often associate “independence” with things like financial security or driving ability – but physical autonomy is just as important – and it could be argued that it’s even more significant. Can you carry your own bags? Reach for a saucepan? Get out of a low chair? These might not be athletic feats, but they’re absolutely foundational to quality of life in your later years.

The reality is, people who lose their independence in later life rarely do so because of chronic illness – it’s far more likely to be assosicated with no longer being able to manage simple daily tasks.

And that’s what makes the case for training movement – not just muscle – so powerful.

Equally, it’s a reason to focus on movement well before it’s required. An investment made just before retirement is better than none at all – but an investment that was made in your 40s or 50s is likely to serve you far better when it’s needed.

What Happens When We Don’t Prioritise These Skills?

Left to its own devices, the body becomes more rigid and less responsive with age. It’s not just your imagination – tightness, stiffness, and slower reflexes really do creep in over time. The good news? These changes aren’t irreversible.

But ignoring them tends to create a slow build-up of problems:

- Less mobility leads to less movement.

- Less movement leads to more stiffness.

- More stiffness increases fall risk.

- One fall leads to injury, hospitalisation, or worse.

It’s a loop – a frustrating one if you’ve experienced it – but it’s also avoidable with a bit of intention and consistency. This is where a great personal trainer can transform your experience.

So, What Can You Do?

Let’s start with this: you don’t need to become a contortionist or expert-level yoga master. But you do need to move with variety, regularly challenge your range of motion, and train your balance in a way that makes sense for your life.

A few simple principles to work with:

- Include multi-directional movement. Linear workouts (like running or cycling) are great, but the body thrives on rotation, side-stepping, reaching, crawling—even playing. Don’t be afraid to explore it.

- Prioritise control, not just effort. Lifting heavier each week is great, but can you move smoothly and with control through the full range?

- Stretch with purpose. Aim to address areas that get tight from your day-to-day (usually hips, shoulders, hamstrings, and spine).

- Train balance like any other skill. Start small – barefoot standing drills, shifting weight from side to side, or single-leg deadlifts. You don’t need to be the most flexible person in the room.

- Use tools that help. Simple Yoga, guided Pilates, mobility flows, foam rollers, resistance bands – they’re all fair game. As ever, the best tool is the one you’ll actually use.

Fitness Lab’s Take

At Fitness Lab, we work with people of all ages and backgrounds – and what we’ve consistently seen is this: the clients who thrive well into their 60s, 70s and beyond are the ones who didn’t just chase aesthetics or performance. They trained for quality of movement.

We like to think of health as a lifelong refinement. It’s not about perfection, or setting PBs into your 80s. It’s about having a body that keeps up with the life you want to live.

If you’re not sure where your mobility, balance or flexibility currently stand, a consultation with a movement specialist can give you real insight – and help you build a plan that fits you. And if you’re already dealing with tightness, pain, or a history of injury? Even more reason to act now.

Final Thought

Mobility. Flexibility. Balance. They are not the flashiest trio in the fitness world, but quietly, they might be the most important. They keep you moving, they keep you resilient, and – perhaps most crucially – they help you stay you as the years go by.

To be absolutely clear – this isn’t a scare tactic into making people think about these factors – it’s simply shedding light on parts of fitness that often fall into the shadows, somewhere behind the weights and the cardio equipment. They deserve an equal footing in anyone’s programme who’s looking to enjoy their later years.

So yes, keep lifting, keep running, keep doing whatever it is you love – but don’t ignore the foundations. Because when the goal is longevity, it’s not just about adding years – it’s about making the most of your body as you age.

Want to futureproof your movement? The Fitness Lab team can help you build a sustainable routine tailored to your needs. Book a consultation today—and take that first step toward a longer, more mobile life.